Childhood, Memory, and Fantasy in "The Ocean at the End of the Lane" and "The Little Prince" (SPOILERS)

The Little Prince

When I teach my Children’s Literature courses, I emphasize a trope that is pretty common amongst books written for or about children: the idea of a fundamental difference between childhood and adulthood, and therefore adults and children. The concept manifests in many ways throughout classic and contemporary stories, and it forms the basis for many of our ideas about how to treat children.

The roots of modern children’s stories

Thinking that children should be protected from knowledge about death, sexuality, or other “adult” concepts is only the most obvious example. The extreme bifurcation of adult and child identities is arguably a product of modern western culture and associated with the emergence of individuality as the ideal social subject and which regards the growth of an individual as the progress from innocence to experience. Critics typically agree that the modern ideal of childhood emerged in the late 1700s and cite Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s theories of education and of individuals as “blank slates” upon which experiences are written. Most kids’ books that are familiar to readers today are firmly entrenched in this Romantic notion of children as having an inherent innocence that must be cherished. Even when challenging that notion, stories are still responding to it and therefore shaped by it.

The oldest children’s stories, aside from nursery rhymes and fairy tales, that continue to be popular date probably to no later than the 1860s, beginning with Alice in Wonderland (1865), which is a perfect example of how the child’s view of the world clashes with what adults think they know; one interpretation of Wonderland is that it is the child’s half-understood manifestation of the adult world; Alice’s development there involves her increasing confidence in her own perspective that is more clear-headed than that of the adult characters. Another well-known example might include Anne of Green Gables (1908), in which the strange red-headed girl with the big imagination transforms the sullen and utilitarian existence of her adoptive mother, teaching her and others how to appreciate nature and the joys of the everyday. Sometimes, the idea that children are somehow better and wiser than adults is held up to scrutiny, particularly in Lemony Snicket’s Series of Unfortunate Events (1999-2006), where the adults’ incompetence and malice are literally unbelievable, as are the children’s cunning and luck.

Alice in Wonderland

Perhaps the most celebrated story about childish wisdom and the folly of adult preoccupations is Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince (1943). Originally, I was going to write this post about Neil Gaiman’s Ocean at the End of the Lane (2013), which, though not a children’s book, likewise explores the way adults fail to see things as clearly as children do. But, having seen The Little Prince movie (2016) recently, I thought it would be interesting to compare how the film works with memory and childhood to how Gaiman does it. Without dwelling too much on plots, Gaiman’s story is about a nameless, quiet, and introspective boy who, having just lost his cat in a car accident and then witnessing the perpetrator’s suicide (crashing his car) retreats into a fantasy world. Guided by the mysterious and ancient girl, Lettie Hempstock, who lives on a farm at the end of the lane, the Narrator unwittingly unleashes a being who terrorizes him and seduces his father. Lettie of course helps to contain this creature. In the course of protecting her friend, she gives him a glimpse into the “Ocean,” during which time he experiences all the knowledge of the universe. The charming-yet-frightening tale is told in first person as the memory of the grown-up Narrator who has returned to the farm after a funeral. After remembering his childhood experience, he is informed by Lettie’s “mother” that this is not the first time he has returned to the farm as an adult, nor will it likely be his last. But he always forgets.

Forgetting and remembering childhood

Like Ocean, The Little Prince movie is about memories of childhood. The movie is a kind of sequel to the book in which the narrator of the novella, the Aviator, tells his story to a lonely child whose single mother is obsessed with planning the Girl’s future success. There is no time in the Girl’s life for play, friends, or imagination. In time, the Girl learns the value of these things through the Aviator’s guidance and the example of the Little Prince. The Prince and the Aviator have a way of seeing beyond what is strictly important (the slogan “be essential” is seen frequently on background posters) and into the joy that comes with imagination and love. A crisis emerges when the Girl learns that the Prince died and never got to return to his home asteroid. She therefore rejects these fanciful stories about the Prince in anguish that they cannot be real if they cannot last forever. Soon after, the Aviator himself falls ill. In a fantasy sequence of a nightmarish world in which adults live only to work and childhood is forbidden, the Girl meets the grown-up Prince who has forgotten everything. Through the Girl’s intervention, the Prince rediscovers his identity and light is restored to the bleak, childless world. In the real world, the Girl makes amends with the Aviator, compiles his notes into a bound copy of The Little Prince, and renews her love of childish play.

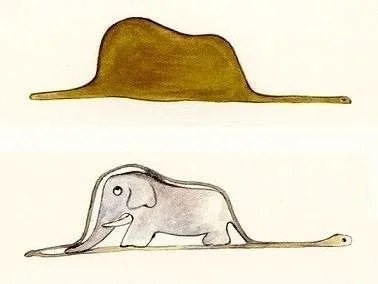

The movie and the original Little Prince begin with the narrator discussing his childhood disappointment with adults’ inability to understand his drawings—what he says is a snake digesting an elephant, they see as a simple hat—and this conflict encapsulates the child-adult binary as a matter of different perspectives. If we follow through the allegory of the book and the film, we can think of the Prince as childhood itself, and his death as the loss of innocence that comes with adulthood. The ability to revive the prince is in turn the memory of childhood. In this reading, the Aviator is not simply recounting his memories of the Prince, but rather accessing his own child self and remembering when he was able to truly see the drawings: The Little Prince not only understands the images, but perceives even more in them than does the adult artist.

Seeing as an adult; seeing as a child

The parallel story introduced in the movie about the Girl serves the same purpose of characterizing the differences between adult and child vision. She is a child who has been encouraged to behave like a grown-up and who has never experienced pure childish joy. The stories of the Prince and her time spent with the Aviator therefore act as her accelerated initiation into childhood. The loss of that newfound innocence takes the form of the Prince’s death and the Aviator’s allusion to his own mortality. These events strip away the Girl’s feelings of childhood, but her immersion into the dream world restores her faith by assuring her that childhood is an immortal part of ourselves and that memory keeps us connected to it. In this reading, the Aviator’s message becomes clear: “growing up isn’t the problem, forgetting is.” The division between child and adult is not insurmountable; rather, adults can access childhood—fantasy, spirituality, joy, love, innocence, play—and retain memories of childhood that guide them through life. But only if they choose to remember.

Ocean is likewise concerned with how the adult’s memory of childhood, with its associations of otherworldliness, can be a guide through the difficult periods one faces as an adult. The frame narrative is crucial to understanding the meaning of the Narrator’s journey. His fantastical experience as a boy begins as a way of coping with a loss of innocence, and his periodic return to the Hempstock farm corresponds to periodic traumas of adulthood. Like the Girl, the Narrator must retreat back into childhood in order to gain the strength to face the harsh realities of life. In both stories, however, fantasy is not simply a coping mechanism, but a way of experiencing a deeper reality than what is visible on the surface. But this is where the meaning of each story diverges, since each conceives of a different origin of the spirit world.

From metaphor to metaphysics

In Ocean, Lettie is an ancient being. She and her Ocean predate the physical world that we live in, and when the Narrator steps into the Ocean, he experiences all the knowledge of the universe in an instant, seeing far beyond what humans can and should see:

I saw the world I had walked since my birth and I understood how fragile it was, that the reality I knew was a thin layer of icing on a great birthday cake writhing with grubs and nightmares and hunger. I saw the world from above and below. I saw that there were patterns and gates and paths beyond the real. I saw all these things and understood them and they filled me, just as the waters of the ocean filled me. (191)

And then there is a forgetting as the boy leaves the Ocean, and a further loss as he grows up and leaves the farm behind. At the end of the novel, before the Narrator once again forgets, he first doubts the truth of his childhood experiences and thinks that his memory is coloured by the fancies of childhood. This suggests that ONLY a child can access these higher truths.

The Little Prince says something a little different. Forgetting is a choice driven by adults’ desires for prestige, wealth, knowledge, and power. Adults see differently, but only because they have been forced to, as is the Little Prince in the movie, having been brainwashed to grow up physically and to forget his adventures. That he once again reverts to his child self with the help of the Girl tells us that children and adults may not be so diametrically opposed if it is possible to transition back and forth. We need only take the effort to remember the experiences of the past. The Aviator clearly sees himself as a child more than as an adult. (As a side note, the popularity of “children’s” entertainment among adults along the lines of revisited fairy tales in movies like Shrek, or the immense success of the superhero genre, should alert us to how artificial is the distinction between what is for children and what is for adults.)

For me, Ocean is frustrating for the way it privileges childhood, fantasy, and spirituality, but relegates these to ephemeral glimpses into a higher truth that ultimately has no place in the mundane. The structure of the novel is symptomatic as well of an attitude toward art as purely escapist. The Narrator is invigorated by each trip to the farm, but the value of those trips lies in their complete dissociation from the pain he experiences in his regular life. The act of forgetting, combined with the superior truth of the fantasy world, indicates that while the everyday is limited and disempowering, it is also the only reality we can ever experience with certainty, and therefore the only one that we can consciously access. Fantasy, or art, therefore only has value for its nebulous relationship to anything concrete. It’s irrelevance to perceivable reality is what makes it powerful and more true. This attitude, I think, diminishes the value of art by considering its appeal to be strictly aesthetic and not at all intellectual. Failing to see the relationship between fiction and reality is a failure to see that all art is also political and social, that its origins lie in the world we inhabit because we create art.

The Little Prince participates in this kind of escapist thinking as well, especially in the movie that disdains pure utility as soul-destroying. But the origins of fantasy are distinct in Ocean and Little Prince; the former describes it as older than anything, while The Little Prince more clearly identifies imagination as a product of human action, a response and a complement to the demands of being “essential.” Ocean does offer the possibility that the Narrator’s experiences are a product of his own mind, but the insistence on the eternity of the Ocean implies that our capability for imagination is itself otherworldly, and therefore beyond the individual will.

Magic or mundane

In either case, Ocean distinguishes art, fantasy, and spirituality from practical concerns and thereby perpetuates an attitude of regarding fiction as merely an escape, rather than seeing it as a function of other aspects of culture. Art is influenced by innumerable human forces, many of which are quite practical: the business of selling art and literature, for example.

On the surface, the Ocean and Prince tell the same kind of story about adults (or the adult-like child in the case of the movie) remembering a purer life of the imagination, namely childhood. A telling connection between these two stories is the lack of proper names given to the characters, and this relates to the stories’ conception of a higher truth existing in the ephemeral worlds of childhood fantasy that lie beyond tangible, pragmatic reality. Naming is a way of categorizing and gaining power over things, and these actions are simply impossible for mortals addressing the eternal (the Businessman’s futile attempt to count and categorize and possess the stars is a metaphor for this absurdity). But in The Little Prince, having a foot in both worlds is possible not just for a brief moment—as is the case literally for the Narrator of Ocean—but is instead a stance one chooses to approach life with everyday.